The Blog of

Holocaust and Antisemitism Foundation Aotearoa New Zealand

“Father knew things would become very bad for Jews..."

‘Father knew things would become very bad for Jews. He wanted to leave for America. But mother said, “No, my brother is here. I want to stay with family.” So, in the end we were sent to a camp in Ukraine.’

In 2018 we visited Rosh HaNikra Kibbutz. It was founded in 1949 by Palmach soldiers, Holocaust survivors and Zionist youth.

We were struck by the kibbutz’ proximity to the Lebanese border. It is just a few hundred metres from the residents’ homes to the Lebanese border fence and, potentially, Hezbollah forces.

While in Rosh HaNikra we captured the accounts of six Holocaust survivors. Here is Ayala’s story.

Survivor to ex-Nazi camp guard: ‘You’ve lived 100 times longer than baby Erika’

Hearing that testimony in Hebrew in a German courtroom was an unforgettable experience and one which I found extremely moving.

First published on Times of Israel

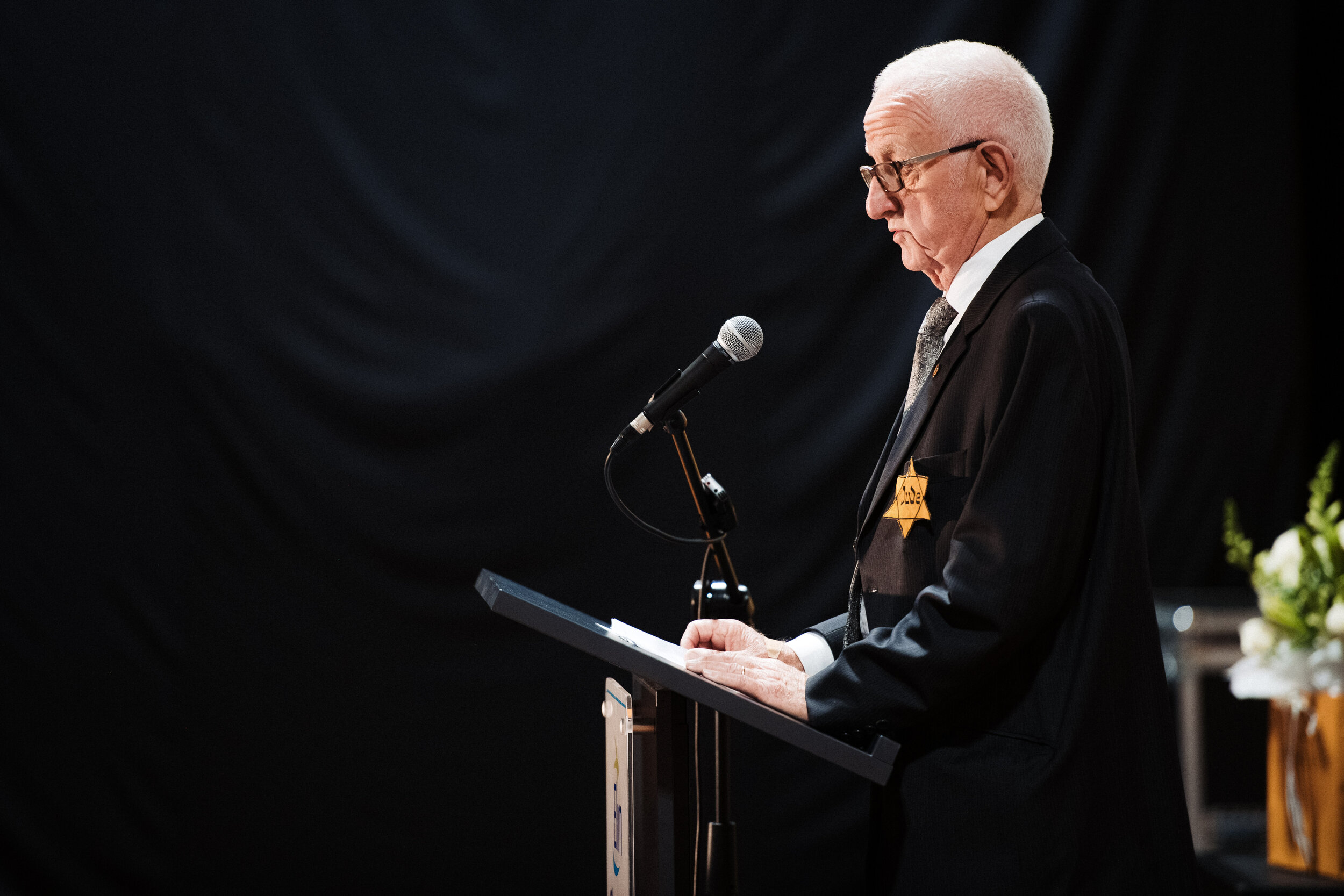

Holocaust survivor Emil Farkas of Haifa was one of the best gymnasts in Israeli sports history. He was Israeli National champion twice and won multiple medals in the Maccabiah Games. But his greatest badge of honor may be the testimony he gave in a German court earlier this month.

At nearly 93, Farkas was the first witness to testify in person — and, apparently, the only Israeli survivor who will do so — at the trial of former S.S. guard Josef Sch ü tz, who served for almost three years in the notorious Sachsenhausen Nazi concentration camp.

Emil was born in February 1929 in Zilina, then Czechoslovakia and today Slovakia, to a middle-class Orthodox Jewish family. His father managed a shoe store that sold orthopedic shoes, and his mother was a nurse. He was the youngest of five siblings: four brothers and a married sister , who was the mother of a one-year-old daughter named Erika.

In the wake of the Nazi invasion of Bohemia and Moravia in March 1939, Slovakia became a separate political entity, ruled by the fascist Slovak Hlinka Guard, in effect a satellite state of the Third Reich. Restrictions on Jewish life became increasingly severe: the yellow badge was made obligatory, and, in March 1942, the first deportations to Auschwitz and Majdanek began, as did the tragedy of Emil’s family.

Among the deportees to Auschwitz were his brothers Bela and Arpad, his sister Peppi and her husband and infant daughter, all of whom were murdered there. Emil was soon sent to two Slovak forced labor camps, first to Novacky and later to Sered, and from there in 1943 or 1944 to three German concentration camps in which the conditions for the prisoners were much harsher, and the chances of survival much slimmer.

The first was Sachsenhausen, where by sheer luck his athletic prowess helped save his life. Every day Emil would get up an hour or so before rollcall, wash himself with snow (in the winter) and do gymnastic exercises with incredible precision. The S.S. guards were shocked by his performance and reported him to the camp commander, who transferred him to work on the “Shoe-Testing Commando,” a group of political prisoners (all non-Jews), whose task was to break in new army boots for the S.S. They did so by marching 30-40 kilometers from 5 a.m. to 5 p.m. each day in a brand new pair of boots, while singing German military songs. Their reward was an extra piece of bread, which helped Emil survive, but if not for his physical strength and stamina, he may have shared the fate of other prisoners who died in the course of these grueling marches.

From there, he was deported to Bergen-Belsen, where he barely survived a savage beating by camp commandant Josef Kramer, a notorious sadist who was hanged by the British after the camp’s liberation. From Bergen-Belsen, Emil was sent to Dachau, where he was liberated by American soldiers, and nursed back to health with the special assistance of a Jewish US Army officer.

Needless to say, testifying at the trial was not an easy task for Emil. Preparing a chronologically accurate narrative of all the different camps and important incidents would have been a challenge for someone half his age, let alone a nonagenarian of almost 93. Luckily, German lawyer Thomas Walther was leading the Farkas “team” — Emil’s relatives and myself invited to accompany him to the trial. Walther, who together with his colleague Kirsten Goetze is responsible for the dramatic change in German prosecution policy vis-à-vis Nazi war criminals that facilitated the belated German trials of the last decade, crafted a dramatic statement for Emil to deliver at the trial.

After relating the major details of his travails in the camps in which he was incarcerated, with a special emphasis on Sachsenhausen, Emil addressed the defendant directly:

“I am sure you must have seen me many times running with the ‘Shoe Commando.’ Today I came to Brandenburg to see you. And therefore I want to ask you: At the end of your one-hundredth year, is your dark secret worth so much to you, that you cannot bring yourself to apologize for your contribution to my suffering? Isn’t it time for you to be brave?

“You didn’t only see me, you also always heard me sing the song I was forced to sing. The name of the song was ‘Erika.’ And thus you heard me sing the second stanza again and again…as I thought about my sister Peppi’s one-year-old daughter, whose name was Erika.

“You Mr. Schütz, you became an adult, living 100 times longer than Erika!”

Hearing that testimony in Hebrew in a German courtroom, read by Emil’s granddaughter’s husband Doron Ben-Ari who had to replace Emil for technical reasons, was an unforgettable experience and one which I found extremely moving.

Emil gave an equally poignant speech on Friday night at the main Berlin synagogue and magnified the impact of his presence at the trial through powerful interviews with the media in which he emphasized the importance he attributes to trials of elderly perpetrators like Schütz, even this many years after the crimes were committed. Our visit with him to Sachsenhausen with Dr. Astrid Ley, the director of the memorial site, also received extensive media coverage.

The hospitality extended by the German government was remarkably gracious — everything possible was done to make Emil and our group feel that we were honored guests. Even more striking was the camaraderie that developed within our delegation under the leadership of Walther, a Righteous Among the Nations German lawyer who has devoted his life to a shared cause. We were a group of Israelis of different persuasions, ages and religious observance, united by our commitment to the mission and thrilled to be able to participate in achieving justice for Holocaust victims and survivors.

The Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated Auschwitz

“…the one and only aim of the military operations was to hold back the inevitable victory by the Soviet Union and the Western Allies long enough to complete the extermination of the Jews.”

A book review by Dr Norman Simms

Jack Fairweather, The Volunteer: The True Story of the Resistance Hero Who Infiltrated Auschwitz.

London: W.H .Allen, 2019; pbk, Penguin, 2020. xix-504 pp. Profusely illustrated with black-and-white maps, drawings and photographs.

This is the story of Witold Pilecki. He was not a Jew and his story becomes one about the Holocaust only as he realizes that by 1942 the Germans had one aim in the Second World War and that was to exterminate the Jews throughout Europe. He volunteers to go into Auschwitz in order to organize a resistance movement among the Polish prisoners, sees the transformation of the concentration camp into an extermination camp, and the shift from Polish and other resistance fighters, Russian POWs and other political inmates to an almost totally Jewish intake of men, women and children to be gassed and cremated.

His original mission was to enlist some of his comrades from various resistance groups and political parties who were opposed to the Nazi and Soviet occupation of Poland. Then gradually, as the Final Solution took shape, he added new aims to his duties. He was to send reports back to Warsaw on what he saw happening, and these reports were to be passed on to the Polish government in exile in London, which was then to seek support from the Allies in aiding the resistance movement. Then these goals changed. At first, he was frustrated by the failure of the leaders of the Polish underground to understand the nature of Nazi cruelty and the large number of murders they were carrying out in Auschwitz.

When he managed to return to Warsaw to argue the case with his comrades, he found them not only incredulous and unwilling to accept that the nature of the war itself was changing. His own informants, as well as his close listening to radio broadcasts from around Europe and his reading of newspapers from London, made him see that the Allies were unable and increasingly unwilling to act on the enormity of the crimes being carried out, especially when the Americans, French and British commanders were being called on to retaliate and take revenge on German and occupied cities for what the Nazis were doing to the Jews.

Moreover, the Russians—that is, Joseph Stalin—had his own plan to seize control of Poland, destroy its bourgeois infrastructure, murder its intellectuals and spiritual leaders, and rule it as a vassal state. Even when the Soviet armies were standing across the Vistula and the Polish patriots came out in an uprising, Stalin held his troops back and let the Germans destroy the city and kill as many civilians as possible. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill made little complaining noises and Stalin made a few token acts, but basically no one was willing to rescue Poland, just as they had no intention of stopping the genocidal murder of millions of Jews. In other words, no one in the world was willing to listen to Witold Pilecki.

Jack Fairweather, a former war correspondent, author of several other books about his experiences in combat zones. Worked with a research team to gather together the information needed to put together The Volunteer. He claims that everything in his biography of Witold Pilecki is based on published evidence, private letters and other documents, interviews with surviving family members and wartime friends, as well as people who knew and collaborated with the resistance hero: and he gives his sources in more than fifty pages of notes. Her also adds a small section listing and describing the main figures who are mentioned in the book and provides an index to aid students seeking to trace out patterns of action, places and ideas, There is also a Selective Bibliography of nearly sixty pages. In brief, this is a serious book to be reckoned with.

And well it should be. Fairweather gives his personal motivation for writing The Volunteer:

I also felt personally challenged by the story—I was the same age as Witold when the war began. I also had a young family, and a home. What would make Witiold risk everything on such a mission and why did his act of volunteering speak so powerfully to me? I recognized in Witold the same restlessness that had led me to war and troubled me ever since. What could Witold teach me about my own struggle to connect? (p.xiii)

Thus, this is no dry, scholarly, objective account. There is justified passion behind Fairweather’s history. He writes with powerful but controlled rage against the silence, inactivity and willful ignorance of the powers that be that did not take Witold Pilecki’s reports into account in planning the end of the war against Nazi Germany and the re-organizing of European states afterwards so that those held responsible for the crimes committed would be punshed and the ideas they represented would be scraped away from the remnants of the civilization the war was conducted to destroy. It was bad enough that throughout the 1930s the Great Powers and the Press trivialized or ignored the rise of Fascism, Nazism and Communism as loathsome ideologies run by insane and wicked dictators. Fairweather sums up his work on the Holocaust: “a failure to recognize and act on its horror” (p. xv). It was for this reason not just a strategic lapse of judgment, as Catrine Clay showed in The Good Germans (reviewed on this Blog on 18 August 2021), in that there were many moments before and during the war when support by the British, French and Americans could have resulted in a coup d’état or assassination of Hitler, but an unforgivable moral failure.

One wonders whether today, two decades into the twenty-first century, these same world leaders, journalists and international organizations are up to preventing another catastrophe of the sort Witold Pilecki bore witness to and warned against. My own feelings are not very sanguine, even in the midst of several concomitant crises—climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic, to name but two.

The narrative opens with the German invasion and occupation of Poland. Though Hitler had already announced his plans to annihilate all of the Jews in Europe, for the Polish people, its army and soon to be resistance organizations, the focus was clearly on salvaging what they could of their own country. They did not see in the Einsatzgruppen and other murder squads taking Jewish men, women and children from conquered Polish villages and towns into the forests to shoot en masse as anything special. The Nazis were also doing the same to Polish priests, teachers and other intellectuals. Witold Pilecki was one of those heroes who failed at this point to rise to the occasion, except as a Polish patriot.

Once sneaked into Auschwitz, which was a relatively small camp, Witold notes down the treatment of prisoners, and the way the kapo system worked; he reported those who were singled out for extra harsh punishments—priests and Jews; who even then made up a small percentage of the total. Individuals who released from the camp to return to Warsaw became the means for sending messages back to the resistance leaders. Yet he noticed more than the tallies who arrived and whose corpses disappeared into the pits and the documents that could be photographed and sent away in microfilm. According to Witold’s diary compiled somewhat later:

Most inmates underwent a personality change upon arriving in Auschwitz. The camp’s unremitting violence broke down the bonds between prisoners, forcing them to turn inward for survival. They became “cantankerous, mistrustful and in extreme cases even treacherous.” (p. 59)

For the non-Jews who formed the majority of prisoners in the early months of his work in the camp, survival remained at least a remote possibility and Witold could call on their nostalgia for home and their desire to inflict revenge on the Nazis through the resistance network he gradually put together. But still the response from Warsaw and London was cautious about mounting an attack on the concentration camp to allow an escape and call attention to what the Nazis were doing which was already way beyond the mere breaking of the Geneva Conventions for treatment of civilians and prisoners of war. The failure of imagination and the lapse in empathy deeply disturbed Witold Pilecki and forced his own personality to change. He was able to reformulate his insight into what was happening around him.

The camp had a way of stripping away pretensions to reveal a man’s true personality. “Some—slithered into a moral swamp,” Witold wrote later, “Others—chiseled themselves a character of finest crystal.” (p. 85)

Some slithered so far down into the swamp as to become Muselmänner, a condition wherein body, mind and soul slip away into virtual nothingness. Witold describes one such inmate reduced to subhuman status:

Even resting, his body ached. His skin was shiny and translucent and sensitive to the touch; his fingers, ears, and nose had turned blue from poor circulation. A telltale sign of his emaciation was the swelling in his legs and feet caused by the fact that it took longer for the water content of the body to reduce than the fats and muscle tissues. It was almost impossible to get his trousers and clogs on in the morning. He could stick his thumb into his legs as if they were made of dough. (pp. 98-99).

As for his mental condition, this poor creature was barely able to think.

His thoughts were jumbled and incoherent, and he sometimes lost consciousness walking back to camp in the evening [after long hours of forced labor in the fields], but he somehow managed to keep marching. Then his brain would reengage, slowly at first, before with a jolt he relized how close he’d come to stumbling… (p. 99)

However, this example of Muselmann is not the severe cases that come soon, especially when the Jews begin to replace the Polish, Russian POWs and others in Auschwitz, that is, those with a modicum of hope for survival. The Jews, as they filled up the camp and quickly were murdered in the gas chambers, had no such hope and most could not call on any inner spiritual strength to keep them going when an inevitable and horrible death was all there was to foresee.

As Witold could see, gradually week by week, the cruelties in Auschwitz became worse, the camp was expanded to receive more Jews, and the hopeless of the situation was manifest. Though his messages convinced a few of his colleagues in the resistance, and we even seen as powerful to stir the conscience and action of the Allies, in the event—nothing. The British hesitated to use horror stories as though they were back in World War One when propaganda claims of German atrocities proved false, did not want to stir up their Arab friends in the Holy Land who would not accept Jews as refugees, and, as always, did not want any more Jewish immigration at home or in the Empire. The Americans and Canadians also hung back for all sorts of reasons, mostly untenable and cowardly. Occasionally a newspaper in the US or Britain placed a notice in about what was not yet called the Holocaust, but hid it away on some back page, and never followed up. Even a delegation of rabbis who marched on Washington, DC and demanded to meet with FDR, went home with a paltry five minute conversation and no promises. Everyone was afraid that revealing the extent of the crimes and using them as a means of justifying attacks on Auschwitz and similar camps “would stir up anti-Semitism at home”. It was no longer a matter of not knowing went on but of ignoring the plight of the Jews.

By the end of August 1941, Churchill understood that the Nazi campaign against the Jews was murderous and unprecedented in scale. But like [the head of the underground, Stefan] Rowecki in Warsaw, he too failed to identify it as genocidal. (p. 173).

This failure was later rationalized away. Theologians argued that it “was possible to live in the ‘twilight between knowing and not knowing’” (p. 174), some grey zone[i] of willful ambiguity and empathy. Hence the saying that “Everyone loves dead Jews but couldn’t care less about living ones”.

The longer the Resistance in Poland held back from a diversionary attack on the gates of Auschwitz so as allow some proportion of the prisoners to escape and to create a newsworthy event, the harder it became for Witold to keep together his small band of men willing to mount an uprising from within. His assistants helped him compile evidence and to even take photographs so that at some point in the not so distant future they could bring the Nazi monsters to account, but the endless delays in agreement from Warsaw and London wore down almost everyone’s willingness to risk their lives in a futile symbolic gesture. Weeks dragged on to months and months to years.

Occasionally someone from Witiold’s secret gang would escape, with a few documents and a memory stocked with precise details, and would sometimes after many months of sneaking from place to place reach London: only to be kept waiting for still more months. Meanwhile the number of murdered Jews mounted from the hundreds of thousands to the millions. More barracks were built, more gas chambers constructed, more crematoria incinerating innocent men, women and children. News filtered in of Nazi reverses, Russian advances, Western Allies landing in Italy and Normandy: but each day thousands of Jews died in Auschwitz and other extermination camps. Malnutrition, overwork, disease and insane medical experiments went on. Witold duly noted each of the new atrocities, recorded the numbers of disappeared and waited for some positive reaction from the Polish Resistance in Warsaw, the Polish government in exile in London, the High Command of Western Allies, the Soviet armies under the direction of a malevolent Uncle Joe Stalin.

The Volunteer is peppered with photographs, drawings and copies of documents, as well as anecdotes on the people who are victims and victimizers, which lightens the heavy load of horrifying information on how the Nazis operated and the resistance and allies prevaricated. This includes glimpses of Witold Pilecki’s family and friends, the people he had to choose more to ignore than not in order to serve the higher cause. The higher cause was to see and empathize with the men and women murdered in atrocious ways so that he could later write up his notes and thus to leave a personal witness to what all too many of his colleagues and supposed allies refused to recognize. Insofar as he ventured to express his psychological insights into whast it felt like to lose one’s basic identity, as well as one’s life’s work, family and sense of being human, he adds to the tragedy of his own life: his inability to convince enough of the right people at the right time to act. The personal frustration and the historical futility of his efforts make this book, as we have sad, something much more than an objective history of Polish Resistance or the Nazi Holocaust. What to him was excruciatingly clear from what he saw and heard in the dark hell of Auschwitz was often incomprehensible to others. In those final months of the war particularly, when a Nazi military defeat seemed inevitable and the time of reckoning approached, the moral failure of those around him became unbearable to Witold.

From the time of the Wannsee Conference in which the Endlösung (Final Solution) was officially formulated as a coherent plan, the inner rage of Witold and his close associates who gathered the information, carried it to the Big Shots, and stood in shocked disbelief when they refused to see what was clear for anyone with half a brain to see and then to act on it. At certain times, too, the leaders of the Reiostance went beyond ignoring Witold and his messengers: they blocked their passage. Not just Witold in his official reports and private journals feels the frustration, but the author of this modern book, Jack Fairweather, keeps repeating the same message that nothing was done when there was time to do something, at most pious words and symbolic gestures.

It was obvious that the Germans meant to kill every Jew they could lay their hands on. The morale of his men had plunged and petty rivalries and squabbles had surfaced as their sense of purpose slipped away. He wasn’t sure how much longer he could hold the underground together. (p.270).

Unable to see what had happened at least by 1942, that whatever other aims Hitler may have had in starting the war in terms of gaining territory and control over vast populations of slave laborers, the reality was that—as secret documents discovered after the war, but also in speeches given by the Nazi elite to their leading generals and Gauleiters (district rulers)—the one and only aim of the military operations was to hold back the inevitable victory by the Soviet Union and the Western Allies long enough to complete the extermination of the Jews. As the end closed down on them, the Nazi leadership, with Hitler in the centre, became manifestly insane, called for the destruction of Germans and Germany in an apocalyptic end to the world, the Gotterdammerung.

As Szmul Zygielbojm, one of only two Jews to sit on the London-based Polish government in exile, said in his suicide note, expressing his utter frustration and disappointment with all the leaders of the war against the Third Reich:

By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people.

And the world’s response: silence.

[i] The Grey Zone, (2001) a film written and directed by Tim Blake Nelson, and starring David Arquette, Steve Buscemi, Harvey Keitel and Natasha Lyonne, telling the story of the Auschwitz Twelfth Sonderkommando unit which, knowing that they like the eleven groups before them would be murdered in turn, staged the only known revolt in the extermination camp. Compare it to Son of Saul ( Saul fia) a 2015 Hungarian film directed by László Nemes, co-written by Nemes and Clara Royer. The “grey zone” represents the dark and gloomy images of the Jewish prisoners assigned to lead their coreligionists into the gas chambers and then, after stripping their bodies of valuables, push them into the crematoria or burning pits nearby; and the horrible situation in which survival depends on collaboration with the enemy.

“We were Jewish so we were taken.”

In 2015 I travelled to Israel to attend the Global Forum For Combatting Antisemitism. While there Dr Efraim Zuroff introduced me to Lydia Brenners, a survivor living in Rishon Letzion. With a colleague I visited Lydia at her home and photographed her while she told her story of survival. Born in Novi Sad, in then Yugoslavia (now Serbia), she survived the 1942 Novi Sad massacre. Watch Lydia’s story of survival.

In 2015 I travelled to Israel to attend the Global Forum For Combatting Antisemitism. While there Dr Efraim Zuroff introduced me to Lydia Brenners, a survivor living in Rishon Letzion. With a colleague I visited Lydia at her home and photographed her while she told her story of survival. Born in Novi Sad, in then Yugoslavia (now Serbia), she survived the 1942 Novi Sad massacre. Watch Lydia’s story of survival.

How long before we can forgive? Nazi-Hunter responds

Lana Hart's op-ed "How long before we can forgive?" raised many important questions regarding the justice system and the attitude toward criminal offenders, among them the recently-deceased former Waffen-SS officer Willi Huber, who achieved hero status among local skiers for his contribution to the establishment of the skiing facilities on Mt. Hutt.

Nazi-Hunter Dr. Efraim Zuroff wrote the following op-ed in response to an article run by Stuff.

Stuff was unwilling to publish.

Willi Huber. Image: Mike Krean STUFF

Lana Hart's op-ed ("How long before we can forgive?" June 7) raised many important questions regarding the justice system and the attitude toward criminal offenders, among them the recently-deceased former Waffen-SS officer Willi Huber, who achieved hero status among local skiers for his contribution to the establishment of the skiing facilities on Mt. Hutt. Ms. Hart brings several examples of people punished for their behavior and a wide range of responses by the criminals to their punishments. And while she notes the importance of the severity of the original wrongdoing in determining a person's punishment, and the principle of proportionality, she fails to understand the significance of Huber's crimes and fails to attribute sufficient importance to his lack of remorse and his obvious adulation for the leader of the most genocidal regime in human history.

When elderly Nazi war criminals are brought to trial these days, the obvious question is whether such trials serve any important purpose, so many years after the crimes were committed when the suspects are frail and elderly. So as a person who has had to answer those questions time and again, I want to share my response with the readers in New Zealand, who have never had to face such dilemmas, since their government is the only Anglo-Saxon country which admitted suspected Nazi war criminals which refused to take legal action against them.

1. The passage of time in no way diminishes the guilt of the perpetrators. Had they been prosecuted immediately after they committed the crimes, it would only have been natural, but the fact that they had eluded justice for decades (for whatever reason) does not in any way reduce their guilt.

2. Old age should not afford protection for those who committed such heinous crimes. Just because a person was able to reach a very advanced age, should not protect them from prosecution. The fact that a person is 90 or 95 or even older, does not turn a murderer into one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

3. We owe it to the victims and their families to bring those guilty of turning innocent men, women, and children into victims, just because they were categorized as "enemies of the Reich," to make a maximum effort to hold those guilty accountable for their crimes.

4. These trials send a powerful message that if you commit such crimes, even decades later, you might be held accountable. This is important because it sends a message to future genocidists and anyone contemplating joining fundamentalist terrorist groups, that while conventional justice is never perfect, the hunts for such criminals go on as long as any of them are still alive.

5. These trials play an important role in the fight against Holocaust denial and distortion. The latter has become a serious problem throughout post-Communist Eastern Europe, where governments seek to hide the participation of their nationals in Holocaust crimes. The former remains a serious problem in Arab and Moslem lands, where it is often government-sponsored and financed.

6. These are the last people on earth who deserve any sympathy, since they had no sympathy on their victims, men, women, and children, some of whom were even older than they are today. When they appear in court these days, they naturally look old and frail (and many try very hard to look even weaker than they actually are), but they didn't commit the crimes they are accused of when they were elderly, but rather many years ago at the height of their physical strength and prowess.

7. Contrary to what many people think or assume, there never was a case of a German or Austrian who was executed for refusing to murder Jews. In many cases, if a person did not want to participate in executions, they could refuse to do so, without any serious penalties.

8. One final point. In all the cases that I have helped facilitate prosecution by finding the perpetrator, there has not been a single defendant, who ever of his or her own volition, expressed any regret or remorse.

Zuroff during an interview at King David Hotel, Jerusalem 2017

Very often, the families of the suspects, accompany them to their trials, and try to create sympathy for them. Invariably, however, the victims have no family members alive who can do so, since they too were murdered by the Nazis and their local collaborators. Consider this article as written by their emissary.

Dr. Efraim Zuroff is the chief Nazi-hunter of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the director of the Center's Israel Office and Eastern European Affairs. He serves on the International Council of the Holocaust Foundation.

Times of Israel: NZ not opening files on ‘resettled’ alleged former Nazi emigres

“Our history was patchy at best,” said Trotter. “In the period between 1933 and 1939 a paltry 1,100 Jews were permitted into New Zealand — and those under the most stringent requirements. The policy was harsh and punitive.”

The widely reported death in New Zealand last year of former Waffen-SS soldier Willi Huber served to awaken the consciousness of New Zealanders to the reality that Nazi war criminals and sympathizers live, or have lived, among them.

Huber, who migrated to New Zealand in 1953, was a keen skier. Often referred to as “a heartland hero” and “the founding father” of the South Island’s Mt. Hutt ski field, he achieved near-legendary status in the skiing fraternity and was lauded by some media. He died never having publicly expressed any remorse for his wartime activities.

Since the end of World War II, New Zealand, like Australia, has served as a sanctuary for war refugees and other displaced persons (DPs), mainly from Europe. But not all, it seems, were honest about their background.

Huber, for example, denied that he had knowledge of any of the atrocities carried out by the Waffen-SS or of the equally well-documented persecution of Jews during the Holocaust. That denial is scorned by prominent members of the Holocaust and Antisemitism Foundation of Aotearoa New Zealand (HAFANZ) who point out that the Nazis’ Waffen-SS was a killing unit that operated outside the legalities of war. They insist that any member of the notorious organization would have been very aware of its modus operandi.

Those sentiments are echoed by HAFANZ International Council member Dr. Efraim Zuroff, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem. A distinguished historian, Zuroff insists that “the unrepentant Huber would have been very aware of the SS atrocities.” He also pointed out reported comments by the Austrian emigre that Hitler was “very clever” and “offered [Austrians] a way out” of the hardships they suffered after World War I.

Zuroff, who has devoted his life to tracking down Nazi war criminals and who these days is referred to as “the last Nazi hunter,” says he and others brought the identities of more than 50 suspected Nazi war criminals (previously reported as 46 or 47) living in the country to the attention of New Zealand’s government when he visited in the early 1990s. (Huber’s name was not among those Zuroff supplied).

“They were all Eastern European and mainly Lithuanian, and I’m sure there were others. Maybe many others,” Zuroff told The Times of Israel via telephone from Jerusalem in late April.

“We have no ability to monitor what happened to them. I know the New Zealand government appointed two detectives to investigate [those named], but the prime minister of the day refused to act on their findings,” Zuroff said.

It remains a sore point with Zuroff that successive administrations in New Zealand have failed to act on those findings.

“New Zealand was the only Anglo-Saxon country, out of Great Britain, the United States, Canada and Australia, that chose not to take legal action after a governmental inquiry into the presence of Nazis. This despite the fact that the lead investigator provided confirmation [of the presence of a Nazi war criminal in New Zealand] that should have been acted on,” Zuroff said.

The investigator he referred to was senior detective Sgt. Wayne Stringer, since retired, who reported that many suspects had already died and that he was able to strike others off the list.

Stringer notably confirmed that one of the names on Zuroff’s list was Jonas Pukas, a former member of the feared 12th Lithuanian Police Battalion, which massacred tens of thousands of Jews during the war.

When questioned at his New Zealand home in 1992, Pukas, then 78, insisted that he had only witnessed the killing of Jews and had not participated. However, he gloated, on tape and on the record, how Jews “screamed like geese” and he laughed when describing how victims “flew in the air” when they were shot.

Despite this, the government at that time decided there was insufficient evidence to charge Pukas with any crime. He died two years later, having lived out his final years in relative peace in his adopted country.

Attempts to reach former detective Stringer were unsuccessful. However, a Daily Mail Australia report from 2012 quotes Stringer as saying, “[Pukas’s] comments still haunt me… I’m confident Mr. Pukas was a war criminal.”

Members of New Zealand’s Jewish community share Stringer’s frustration. They want the list of names identifying Nazi war criminals and sympathizers — as supplied by Zuroff almost three decades ago — declassified so that those identified can be named. Though Zuroff himself is the one who supplied the names, he told The Times of Israel that he declines to publish them himself, as “that was the duty of the New Zealand government.”

Those identified relinquished any right to privacy, for themselves or their families, when they entered the country under false pretenses

A senior member of HAFANZ who asked to remain anonymous described the outstanding issue as New Zealand’s legacy of shame.

“Government bureaucrats in successive administrations wanted to be satisfied that declassifying the documents supplied and naming those identified would be in the public interest and would not breach privacy issues,” the HAFANZ official said. “Our answer to that is, the truth [about what happened and who was responsible] is surely in the public interest. As for privacy issues, those identified relinquished any right to privacy, for themselves or their families, when they entered the country under false pretenses.”

Given the amount of time that has elapsed since the war’s end and the fact that most, if not all, of the named parties are now dead, privacy issues today would be more likely to apply to the surviving relatives of those named.

The HAFANZ member said he hoped publicity would prompt New Zealand’s current government to do the decent thing and declassify the documents. “It’s only fair,” he said.

Historian and HAFANZ co-founder Dr Sheree Trotter said it was difficult to explain the government’s lack of response on identified war criminals — especially as it was so out of step with the country’s allies.

“The specific case of Willi Huber could be explained by a number of factors,” Trotter said. “Many New Zealanders struggle to face our own colonial past where injustices and crimes were perpetrated by our forebears. It’s easier [for some] to take the view that we should just move on.”

Critics of the lack of response by successive governmental administrations are annoyed that Jewish refugees, including Holocaust survivors, had to jump through many more hoops to be admitted into New Zealand than did Nazi sympathizers, war criminals and other undesirables.

“Our history was patchy at best,” said Trotter. “In the period between 1933 and 1939 a paltry 1,100 Jews were permitted into New Zealand — and those under the most stringent requirements. The policy was harsh and punitive.”

Hungarian-born historian and author Ann Beaglehole agrees. “Jews were considered extremely undesirable settlers in the 1930s and 1940s,” she said.

Beaglehole summarizes the recent history of Jews in her adopted homeland in an essay titled “The Response of the New Zealand Government to Jewish Refugees and Holocaust Survivors, 1933-1947.” It is a damning portrayal of attitudes of the day.

Hungarian-born historian and author Ann Beaglehole.

“A small number of Jewish refugees… admitted before the outbreak of war put a stop to most immigration… Government policy was primarily concerned with the maintenance of New Zealand’s ethnic homogeneity, with Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors regarded as undesirable settlers,” Beaglehole writes.

In her acclaimed book “Refuge New Zealand: A Nation’s Response to Refugees and Asylum Seekers,” Beaglehole addresses some of the security issues New Zealand faced when selecting displaced persons for resettlement there.

“Security issues had to be considered. Selectors [of suitable DPs] were urged to take particular care with security screening to try to prevent war criminals, Nazi collaborators and traitors from entering New Zealand,” Beaglehole said.

Beaglehole quotes in the book a Department of Labour and Employment official as saying, “There will be Nazi sympathizers and communists amongst those [applying]. We want neither.”

“Despite New Zealand’s vigilance, some former Nazis were resettled in New Zealand,” the book continues. “A 1953 [Department of] Internal Affairs report noted: ‘For some time it has been fairly clear that wartime activities of a certain number… of DPs in New Zealand were highly dubious.’ It recommended that those concerned should not be naturalized and should be threatened with deportation.”

Of course, that never happened.

New Zealand’s current government appears no more enthusiastic about addressing the issue of resettled Nazi war criminals or declassifying documents relating to them than were past administrations.

NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern speaks to journalists during a press conference at the Justice Precinct in Christchurch on March 20, 2019. (Marty MELVILLE / AFP)

A formal request by The Times of Israel to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern resulted in an admission that she “has no knowledge of suspected Nazi war criminals being admitted into New Zealand following WWII.”

Ardern’s press secretary, Zach Vickery, suggested the writer contact Immigration New Zealand for the requested information. A formal request to that ministry resulted in a similar response from Immigration New Zealand General Manager Border and Visa Operations Nicola Hogg.

“Immigration New Zealand [INZ] has no record of visa applications for individuals entering New Zealand after WWII where Nazi war criminals or sympathisers were identified during processing,” said Hogg.

“INZ is unable to assess whether it holds any historical documents relevant to your request without specific details of named individuals. However, if you are able to provide individual names or cases, INZ may be able to investigate further,” she said.

This writer replied that Hogg’s response indicated “she may not grasp the fact that Nazi war criminals and sympathizers would be highly unlikely to mention their dubious ‘credentials’ on their visa applications.”

No further response was forthcoming.

New Zealander Lance Morcan is an independent author, film producer and screenwriter.

NZ Green MP’s Genocidal Cry Against the Jewish State

NZ Green Party MP Ricardo Menendez recently tweeted an image of himself and fellow Green MPs Chloe Swarbrick and Golriz Ghahraman at an anti-Israel protest in Auckland. The text accompanying his tweet: From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free!

Antisemitism is ancient, multifaceted and mutates readily. As has been observed by the Holocaust Foundation, and by international experts in the field, anti- Zionism is one of the most common and effective forms of antisemitism in the present age. Anti-Zionism is frequently granted a free pass, particularly when presented in the garb of human rights. Where open hatred of the Jew is frowned open, hatred for the Jewish state is permissible.

NZ Green Party MP Ricardo Menendez recently tweeted an image of himself and fellow Green MPs Chloe Swarbrick and Golriz Ghahraman at an anti-Israel protest in Auckland. The text accompanying his tweet:

From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free!

This is an unequivocal call for the destruction of the Jewish state. A jihadic slogan, frequently heard at terror supporting protests, From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free! is a call for the land between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean Sea to be free of Jews. It is a cry for ethnic cleansing and an implicit call for genocide.

Greens are on record as being in support of a negotiated two-state solution to the Israel-Palestinian conflict. Has that policy position now been superseded by an antisemitic call for ethnic cleansing?

Many New Zealanders have been alarmed by moves to introduce hate speech legislation. Yet even strong defenders of free speech recognise that incitement to violence should be disallowed. Remarkably, NZ’s Green Party is understood to be supportive of proposed hate speech legislation and yet in practice is willing to engage in, and tolerate within its ranks, actual hate speech,

The Holocaust and Antisemitism Foundation, Aotearoa New Zealand calls on New Zealanders to object to the mainstreaming of antisemitism by our Members of Parliament.

Holocaust Memorial Day 2021, Botany, Auckland

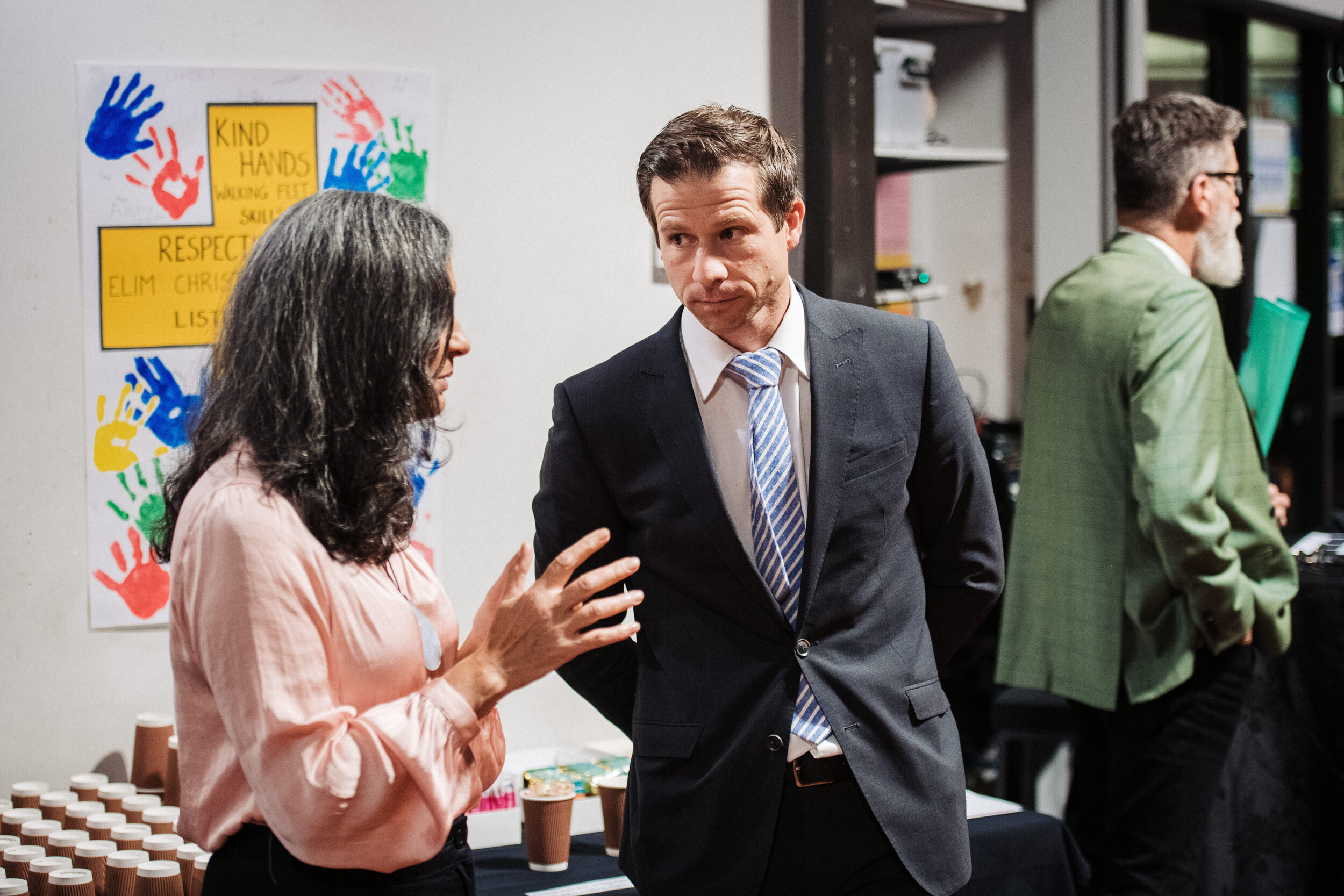

Over 260 attended the Yom HaShoah 2021 and “Auschwitz. Now.” opening event held at Elim Christian College. Guest speakers included H.E. Ambassador Ran Yaakoby, survivor Robert Narev OMNZ, Dr Sheree Trotter, Dame Lesley Max and Elim’s Murray Burton MNZM and Ps Steve Green. Rebbetzin Deb Levy Friedler MC’d the event.

The Holocaust Foundation held an event for Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Memorial Day) and the opening of the “Auschwitz. Now.” exhibition at Elim Christian College on 8 April.

Guest speakers included H.E. Ambassador Ran Yaakoby, survivor Robert Narev OMNZ, Dr Sheree Trotter, Dame Lesley Max and Elim’s Murray Burton MNZM and Ps Steve Green. Rebbetzin Deb Levy Friedler MC’d the event.

MP’s in attendance included Christopher Luxon, Michael Wood, Chris Penk and Simon O’Connor.

Principal Murray Burton MNZM presented the Israeli Ambassador with a gift as an expression of Elim’s support for Israel and Jewish people. Elim has sent 200 senior students to Israel in past years.

The event was well supported with 260 in attendance.

The exhibition remained open to the public till Sunday 11 April.

Dr Sheree Trotter addressed more than 400 students during the exhibition’s tenure at Elim.

Scroll down to view the full gallery of event images.

Event images courtesy of Smoke Event Photography

An 80-year search for ‘the student K,’ murderer of Jewish babies

This is a story about a Nazi war crimes investigation that began in 1945 and continued intermittently until 2021. It is a good example of why, even today, it is still important to try and achieve justice.

First published by Times of Israel

This is a story about a Nazi war crimes investigation that began in 1945 and continued intermittently until 2021. It concerns the brutal murder of Jewish infants in Raseiniai (Rasein in Yiddish and Hebrew), Lithuania, and is a good example of why, even today, it is still important to try and achieve justice. This week we observe the International Holocaust Remembrance Day mandated by the United Nations in 2005, and therefore it is an especially appropriate time to share this episode in the ongoing efforts to hold the perpetrators of Holocaust crimes accountable.

In 1945, Leib Kunichowsky, a Lithuanian Jewish survivor of the Kovno (Kaunas) Ghetto, began to record the testimonies of the few Holocaust survivors from the local provincial communities. This was a particularly important mission in view of the extremely high murder rate in those towns and villages. Of the 220,000 Jews who lived in Lithuania under the Nazi occupation, 96.4% (212,000) had been murdered, but most of the survivors were from the large ghettos of Vilna (Vilnius), Kovno (Kaunas), and Shavli (Siauliai). Approximately 100,000 Jews lived in the provincial communities, which had been so terribly decimated at an even higher rate. For the next four years, initially in Lithuania and later in the Displaced Persons camps in Allied-occupied Germany, Kunichowsky sought out the few survivors and recorded their testimonies in Yiddish in longhand, making sure that both he and the survivors personally signed each and every page. The result of this mission was a collection of 1,684 pages of testimony in Yiddish that contained much priceless information about the fate of the provincial Jews.

Lithuania’s enthusiastic local collaborators

Kunichowsky’s collection also had another unique aspect, which made it even more valuable. Unlike many other testimony projects conducted at that time, he focused inordinate attention on the identity of the perpetrators, which in Lithuania was of particular significance due to the critical role played by local Nazi collaborators in the murders, especially in the provinces. And since, in almost all those locales, those who participated in the murders were often known to the local Jews, the survivors were able in many cases to identify their tormentors. The result was that Kunichowsky’s collection contained the names of 1,284 Lithuanian perpetrators, a veritable treasure of information of great potential value for prosecutors and investigators.

I first learned of the existence of the testimonies in 1980, while working as a researcher in Israel for the US Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, which prosecuted the Nazi war criminals who had immigrated to the United States after World War II. They were very interested in obtaining access to the testimonies. The problem was that Kunichowsky had insisted his collection be published in its entirety, and until that took place, he was not willing to share any of its contents with anybody, for any reason. Thus for 40 years, it remained completely inaccessible. This obstacle was only overcome almost a decade later in late 1989, when Prof. Dov Levin, the leading expert on the Holocaust in the Baltics and, like Kunichowsky, a survivor of the Kovno Ghetto, persuaded him to donate his collection to the Yad Vashem Archives.

Once the collection had been deposited in the archives, I immediately set out, with the help of my father, to extract all the names of perpetrators in the testimonies, a total of 1,284 names, of which only 121 were already known from other sources. My next step was to try and discover whether any of these criminals had emigrated to Western democracies. (By this point, it was common knowledge that thousands of Eastern European Nazi collaborators had immigrated postwar to the U.S., Canada, U.K., Australia, and New Zealand posing as innocent “refugees:”) This was possible by cross-referencing immigration data available in the International Tracing Service (ITS) records (also at Yad Vashem) with the testimonies, and in that manner I was able to find many dozens of suspects who had fled to the West and might still be alive.

Incredible cruelty

The testimonies in the Kunichowsky collection provide vivid details of the implementation of the Final Solution in Lithuania, the exceptionally critical role played by the local collaborators who were by far the majority of the killers, and the incredible cruelty of some of the perpetrators.

One of the testimonies which particularly upset me and clearly reflected the latter phenomenon was that of a woman named Dina Zisa Flum from the town of Rasein (Raseiniai), who survived by hiding in a pile of hay close to the pit where the murders took place in August 1941. In her testimony of April 4, 1945, she related that “While lying on the hay, I clearly saw two women standing near the pit [which the victims fell into after being shot-E.Z.] smashing the skulls of small children with a large rock or hitting the children by smashing their heads together. One of the women was the student K——.”

That image of “the student K.” has not left me ever since. Her family name (which shall remain under wraps for obvious reasons) indicated that she was single, but the witness did not indicate her first name. Even though I did not have her full name, I searched for her in the ITS records and found two possible candidates born two years apart who could fit the description and had fled Lithuania shortly after the war. The names were submitted about thirty years ago to the Nazi war crimes unit established in her emigration destination, but we never received any information on whether the local authorities had been able to ascertain whether either of the two female immigrants might be the infamous ‘student K.’

Fast forward another 30 years to the present. Our researcher on a different project, Dr. Abbee Corb, comes across my list of potential suspects, which included the two young women who might have been “the student K.,” and finds one of them alive and healthy at 97, residing not that far from her own home. The question then became whether we could verify her first name. In theory, the best solution would have been to send a trustworthy Lithuanian to speak to elderly residents of Raseiniai who may have known “the student K” or her family. But that town is now the COVID-19 capital of Lithuania, so no one is willing to take on the mission. Appeals on social media to find someone with links to Raseiniai residents also failed to produce a solution, but archival research appears to indicate that the elderly woman Abbee found might well be the criminal we have been looking for. Can we confirm it before the pandemic ends or she dies?

I cannot be sure, but I think our efforts, which hopefully will be successful, send an incredibly powerful message: If you brutally murder Jewish babies, there will be Jews, even 80 years later, who will strive to make sure you are held accountable. And that remains an important message in 2021 as well.

–

Dedicated to the memory of the Jewish babies brutally murdered in Raseiniai, Lithuania in August 1941.

Dr Efraim Zuroff is the chief Nazi-hunter of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the director of the Center's Israel Office and Eastern European Affairs. He serves on the International Council for the Holocaust and Antisemitism Foundation, Aotearoa New Zealand